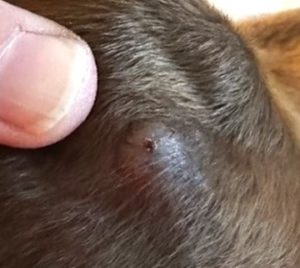

Hazel presented to Hawthorne Hills Veterinary Hospital on September 16th, 2024 for evaluation of a small growth on her left ear that the owner had just noticed a little bit ago. The growth wasn’t seeming to bother Hazel at all as she wasn’t scratching at it or excessively shaking her head, but her owner still wanted it checked out. Hazel was seen by Dr. Andy Pietraniec. On exam, Hazel had what appeared to be a small 1cm x 1cm raised dermal mass right in the middle of the back side of her ear. The mass was hairless, a little red, non-ulcerated, firm on palpation, and did not seem painful to Hazel when it was being examined. After discussing history, clinical signs, and confirming that there were no other areas of concern with the rest of Hazel’s physical exam, a fine-needle aspirate of the mass was recommended.

A fine-needle aspirate (or FNA for short) is a procedure where the veterinarian will take an appropriately sized needle and use it to poke into the mass from the outside, and once in the mass the needle is redirected in multiple different directions around the mass to collect the sample.

A fine-needle aspirate (or FNA for short) is a procedure where the veterinarian will take an appropriately sized needle and use it to poke into the mass from the outside, and once in the mass the needle is redirected in multiple different directions around the mass to collect the sample.

The goal is that as the needle is advanced into and out of the mass at these various angles, some of the various cells and tissues making up the mass become lodged into the central opening of the needle. The needle is then removed and attached to a syringe full of air, and the contents of the needle that were collected from the mass are expelled out onto a slide for further examination under a microscope.

Here’s the appearance of the initial skin nodule on the outer ear flap.

The hope is that this “snapshot” of the cells in the mass will tell us more about what this mass is, and more importantly if the cells seen in it demonstrate any criteria of malignancy. While that is always the goal of an FNA, it is important to note two important limitations to this diagnostic method:

1.) not all masses will aspirate well. Some cell types and masses will not provide a good FNA sample simple because of their cellular make-up, and a collected sample will likely not show an accurate representation of what is there. And

2.) While the needle is being redirected all around the mass, there is no guarantee that the sample will truly show everything that is going on with that mass. A good example is that if the mass is caused by a couple infectious agents, unless that agent is present in the cells collected by the needle then they will not show up on the slide.

FNAs are a great first diagnostic test for masses because they can usually be done without needing to sedate the animal, and they are minimally invasive. If a FNA sample comes back as either non-diagnostic or as something more concerning, a full biopsy of the mass may be recommended and this usually requires at least sedation, if not full anesthesia.

The FNA result for Hazel came back with relatively low cellularity, but based on the presence of mild lymphocytic inflammation, the pathologist was suspicious that it could be a cutaneous histiocytoma. A cutaneous histiocytoma is a benign tumor that is usually associated with young animals that is solitary, pink, hairless, and can grow very quickly over a few weeks. The good news is that these tumors usually spontaneous regress on their own with no treatment after a couple of months. After we conveyed these results to Hazel’s owner, we chose to monitor its progression over the next month and two and hopefully it would slowly go away on its own.

About 2 months later, Hazel came back in to have the mass looked at again, and it had actually gotten a little bit bigger since September, but otherwise hadn’t changed in appearance or discomfort for Hazel.

About 2 months later, Hazel came back in to have the mass looked at again, and it had actually gotten a little bit bigger since September, but otherwise hadn’t changed in appearance or discomfort for Hazel.

Another FNA of the sample was collected to again look for any underlying changes or causes to this mass on the ear; this time the sample showed something a bit different. There were some slender rod-shaped negative staining structures in the cytoplasm of a few histiocytic cells: a probable mycobacterial infection, and based on the location most likely a Canine Leproid Granuloma.

Here is a photo of the ear nodule after several months and the granuloma has formed.

Mycobacterium are pathogens that survive inside of certain white blood cells that are usually meant to kill the pathogen. Once the white blood cell takes up the pathogen, it is built to survive attempts at destruction inside the cell, and effectively shuts off the cell’s ability to migrate to the spleen where they are usually destroyed and recycled back into new cells. Once Mycobacterium take over control of these white blood cells, they can replicate freely for further infection.

What happened in Hazel’s case (and in a lot of cases with mycobacterial infection) is that the body turns the area into a granuloma, basically attempting to “wall-off” the disease by surrounding it with other cells and covering it with a thick, fibrous capsule to prevent further spread. Mycobacterial infections are really uncommon in the state of Washington, and based on the lesion location and distribution of cases across the world it appears most likely that biting insects are a contributing factor in the spread of the disease.

Based on recommendations from a local veterinary dermatologist, Hazel was started on a systemic antibiotic called doxycycline and put on a parasite preventative that also has a bite-repellent effect since it has been associated with insect bites. She has been on this treatment since the start of December and is currently doing really well.

Based on recommendations from a local veterinary dermatologist, Hazel was started on a systemic antibiotic called doxycycline and put on a parasite preventative that also has a bite-repellent effect since it has been associated with insect bites. She has been on this treatment since the start of December and is currently doing really well.

Through this whole process, Hazel has been very tolerant about the vet visits and testing. She has kept her love of hiking, camping, and long walks on the beach. And she loves to finish each day cuddled up with a nice warm fleece blanket next to her mom. Hopefully the granuloma begins to shrink in size until it eventually goes away on its own.

~ by Dr. Andy Pietraniec ~

LINKS:

Texas A&M Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Lab: https://tvmdl.tamu.edu/case-studies/leproid-granuloma-in-a-boxer-dog/

Under the Microscope: https://www.publish.csiro.au/ma/pdf/ma04438

National Library of Medicine: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10331390/

WAG! https://wagwalking.com/condition/canine-leproid-granuloma-syndrome